We are an exploratory species, just past the solar system now, but perhaps one day we will look back and call our galaxy merely the first. There are many problems to solve along the way, and today we will look at one very small one. How do we assign IDs to devices (or any object) so the IDs are guaranteed to always be unique?

Being able to identify objects is a fundamental tool for building other protocols, and it also underpins manufacturing, logistics, communications, and security. Every ship and satellite needs an ID for traffic control and maintenance history. Every radio, router, and sensor needs an ID so packets have a source and destination. Every manufactured component needs an ID for traceability. And at scale, the count explodes: swarms of robots, trillions of parts, and oceans of cargo containers moving through a civilization’s supply chain.

One of the key functions of an ID is to differentiate objects from one another, so we need to make sure we don’t assign the same ID twice. Unique ID assignment becomes a more challenging problem when we try to solve it at the scale of the universe.

But we can try.

Random

The first and easiest solution is to pick a random number every time a device needs an ID.

This is so simple that it is likely the best solution; you can do this anytime, anywhere, without the need for a central authority or coordination of any kind.

The big issue, though, is that it’s possible for two devices to pick the same ID by chance. Fortunately, we have complete control over the size of the random number, and by extension, the probability of a collision. This means we can make the likelihood of a collision functionally zero.

You may say that “functionally zero” is not enough, that although the probability is small, it is not actually zero, and so you are concerned. But consider this example: The probability of you being struck by a meteorite right now is small but non-zero, and you might even call that a “reasonable” (if paranoid) concern. But are you worried that every human on Earth will be hit by a meteorite right now? That probability is also non-zero, yet it is so infinitesimally small that we treat it as an impossibility. That is how small we can make the probability of an ID collision.

So how small does this probability need to be before we are comfortable? It will be helpful to reframe the question: How many IDs can we generate before a collision is expected?

The most recent version of Universally Unique Identifiers (UUIDs), which are a version of what we have been describing, uses 122 random bits. Using the birthday paradox, we can calculate the expected number of IDs before a collision is $\approx 2^{61}$.

Is this high, or is it low? Is it enough to last the galaxy-wide expansion of the human race up to the heat death of the universe? Let’s try to calculate our own principled number by looking at the physical limits of the universe.

Universal limit

The paper “Universal Limits on Computation” has calculated that if the entire universe were a maximally efficient computer (known as computronium), it would have an upper limit of $10^{120}$ operations before the heat death of the universe. If we assume every operation generates a new ID, then we can calculate how large our IDs need to be to avoid a collision until the universe runs out of time.

Using approximations from the birthday paradox, the probability of a collision for $n$ random numbers across a set of $d$ values is

\[p(n, d) \approx 1 - e^{-\frac{n(n-1)}{2d}}\]We want a probability of $p = 0.5$ (this is a close approximation for when a collision is “expected”) for $n = 10^{120}$ numbers, so we can solve for $d$ to get

\[d \approx -\frac{n(n-1)}{2 \times \ln(1 - p)} = -\frac{10^{120}(10^{120}-1)}{2 \times \ln(1 - 0.5)} \approx 10^{240}\]This is how large the ID space must be if we want to avoid a collision until the heat death of the universe. In terms of bits, this would require $\log_{2}(10^{240}) = 797.26$, so at least 798 bits.

This is the most extreme upper limit, and is a bit overkill. With 798 bits, we could assign IDs to literally everything ever and never expect a collision. Every device, every microchip, every component of every microchip, every keystroke, every tick of every clock, every star and every atom, everything can be IDed using this protocol and we still won’t expect a collision.

Reasonable limits

A more reasonable upper limit might be to assume that every atom in the observable universe will get one ID (we assume atoms won’t be assigned multiple IDs throughout time, which is a concession). There are an estimated $10^{80}$ atoms in the universe. Using the same equation as above, we find that we need 532 bits to avoid (probabilistically) a collision up to that point.

Or maybe we convert all of the mass of the universe into 1-gram nanobots? We would have $1.5 \times 10^{56}$ bots, which would require IDs of 372 bits.

We now have four sizes of IDs we can choose from, depending on how paranoid we are:

- 798 bits from computronium

- 532 bits for atoms

- 372 bits for 1-gram nanobots

- 122 bits from UUIDs

Note that this has assumed true randomness when generating a random number, but this is sometimes a challenge. Many random number generators will use a pseudo-random number generator with a non-random seed. You want to ensure your hardware is capable of introducing true randomness, such as from a quantum source, or by using a cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator (CSPRNG). If that is not available, using sensor data, timestamps, or other non-deterministic sources can help add additional randomness, but, it will not be pure randomness and therefore it will increase the probability that IDs collide. It would probably be a good idea to ban any IDs that are “common”, such as the first 1,000 IDs from every well known pseudo-random generator, the all-zeros ID, the all-ones ID, etc..

But what if we are exceptionally paranoid and demand that the IDs are theoretically guaranteed to be unique? None of this probabilistic nonsense. That will take us on a journey.

Deterministic

As usual, let’s start with the easiest solution and work from there.

All the code for visuals, simulations, and analysis can be found at this github repo.

Let’s create a single central computer that uses a counter to assign IDs. When someone requests an ID, it assigns the value of its counter, then increments the counter so the next ID will be unique. This scheme is nice since it guarantees uniqueness and the length of the IDs grows as slow as possible: logarithmically.

If all the 1-gram nanobots got an ID from this central computer, the longest ID would be $\log_2(1.5 \times 10^{56}) = 187$ bits. Actually, it would be a tiny bit longer due to overhead when encoding a variable-length value. We will ignore that for now.

Ok, there are serious issues with this solution. The primary issue I see is access. What if you’re on a distant planet and don’t have communication with the central computer? Or maybe your planet is so far from the computer that getting an ID would take days. Unacceptable.

In order to fix this, we might start sending out satellites in every direction that can assign unique IDs. Imagine we send the first satellite with ID 0, then the next with 1, and keep incrementing. Now people only need to request an ID from their nearest satellite and they will get back an ID that looks like A.B, where A is the ID of the satellite and B is the counter on the satellite. For example, the fourth satellite assigning its tenth ID would send out 3.9. This ensures that every ID is unique and that getting an ID is more accessible.

But why stop at satellites? Why not let any device with an ID be capable of assigning new IDs?

For example, imagine a colony ship is built and gets the sixth ID from satellite 13, so it now has an ID of 13.5. The colonists take this ship to the outer rim, too far to communicate with anyone. When they reach their planet, they build construction robots which need new IDs. They can’t request IDs from a satellite since they are too far, but they could request IDs from their ship. The construction bots get IDs 13.5.3 and 13.5.4 since the ship had already assigned 3 IDs before this time and its counter was at 3. And now these robots could assign IDs as well!

This does assume you always have at least one device capable of assigning IDs nearby. But, if you are in conditions to be creating new devices, then you probably have at least one pre-existing device nearby.

Let’s call this naming scheme Dewey.

Dewey

How does Dewey compare to the random-IDs in terms of bits required?

If an ID is of the form A.B. ... .Z, then we can encode that using Elias omega coding. For now we will ignore the small overhead of the encoding and assume each number is perfectly represented using its binary values, but we will add it back in later. That means the ID 4.10.1 would have the binary representation 100.1010.1, which has 8 bits. We can see how each value in the ID grows logarithmically since a counter grows logarithmically.

How the IDs grow over time will depend on what order IDs are assigned. Let’s look at some examples.

If each new device goes to the original device, creating an expanding subtree, then the IDs will grow logarithmically. This is exactly the central computer model we considered earlier.

If we take the other extreme, where each new device requests an ID from the most recent device, then we form a chain. The IDs will grow linearly in this case.

Or what if each new device chooses a random device to request an ID from? The growth should be something between linear and logarithmic. We will look more into this later.

We might also ask, what are the best-case and worst-case assignment trees for this scheme? We can just run the simulation and select the best or worst next node and see what happens. Note that there are multiple ways to show the best-case and worst-case since many IDs have the same length, so we arbitrarily have to pick one at a time, but the overall shape of the tree will be the same. Also note that this uses one-node lookahead, which might fail for more complex schemes, but is valid here.

We see one worst-case tree is the chain. This best-case tree for Dewey seems to have every node double its children, then repeat. This causes it to grow wide quite quickly. This indicates that this scheme would be great if we expect new devices to primarily request IDs from nodes that already have many children, but not great if we expect new devices to request IDs from other newer devices (the chain is the extreme example of this).

Here is the best-case at a larger scale to get a more intuitive feel for how the graph grows. What we care about is the fact that it is a fairly dense graph, which means this scheme would be best if humans use a small number of nodes to request IDs from.

It’s annoying that the chain of nodes causes the ID to grow linearly. Can we design a better ID-assignment scheme that would be logarithmic for the chain as well?

Binary

Here is another attempt at an ID-assignment scheme, let’s see if it will grow any slower.

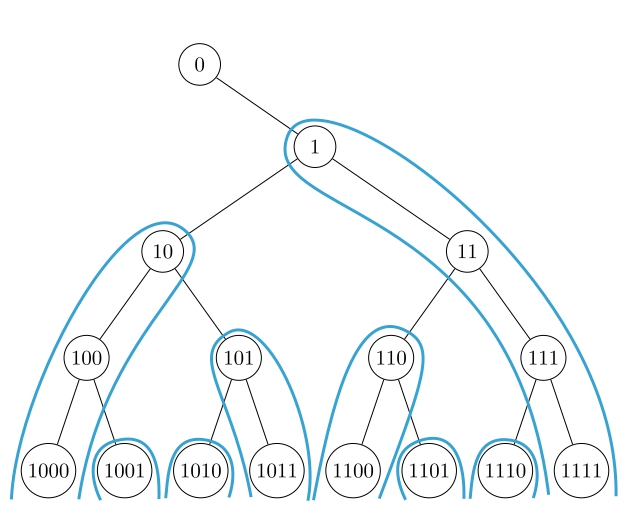

Take the entire space of IDs, visualized as a binary tree. Each device will have an ID somewhere on this tree. In order to assign new IDs, a device will take the column below it (columns alternate from left or right for each device) and assign the IDs in that column. With this scheme each node has a unique ID and also has an infinite list of IDs to assign (the blue outline in the figure), each of which also has an infinite list of IDs to assign, and so on.

And now we can look at how it grows across a subtree and across a chain.

Both cases grow linearly. This is not what we were looking for. It’s now worth asking: Is this scheme always worse than the Dewey scheme?

If we look at the worst-case and best-case of this scheme, we notice that the best-case will grow differently then Dewey.

And the best-case at a larger scale.

It grows roughly equally in all directions. The depth of the best-case tree grows faster than Dewey, which means this scheme would be better for growth models where new nodes are equally likely to request from older nodes and newer nodes. Specifically, the best-case tree grows by adding a child to every node in the tree and then repeating.

So this scheme can be better for some trees when compared to Dewey. Let’s keep exploring.

Actually, there is a scheme that looks different, but grows the same as this one.

2-Adic Valuation

If each ID is an integer, then a node with ID $n$ would assign to its $i$th child the ID $2^i(2n+1)$. Essentially, each child will double the ID from the previous child, and the first child has the ID $2n+1$ from its parent. This is a construction based on 2-adic valuation.

You can prove that this generates unique IDs by using the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic.

You can change the memory layout of this scheme pretty easily by using $(i, n)$ as the ID instead of $2^i(2n+1)$. Now the sequential child IDs of a node will grow logarithmically instead of linearly. This feels very similar to Dewey.

That’s all a bit complicated, but essentially we can say that this is an alternative representation of the Binary scheme we already looked at. But we want to explore new schemes that might have better memory growth characteristics.

Token

Let’s try to reverse-engineer a scheme that can grow logarithmically for the chain tree.

We know that a counter grows logarithmically, so ideally the ID would only increment a counter when adding a new node.

One idea is to have a token that gets passed down to children with a hop-count attached to it. But what happens when a device gets a new ID request and it doesn’t have a token to pass? We will have a token index which increments each time a parent has to create a new token. The new token will then be appended to the parent ID. So the chain of three will look like [], [(0,0)], [(0,1)], as the root node has no token, then the first child causes the root to generate token, then the next hop gets the token passed down to it with an incremented hop count. If the root node had two more ID requests, it would generate [(1,0)] and [(2,0)], incrementing the first value to produce unique tokens. Each ID is a list of (token-index, hop-count) pairs, ordered by creation. Let’s get a better idea of what this looks like by looking at a simulation.

Here we have the expanding subtree, the chain, and one of the best-cases.

We can see that IDs are a bit longer in general since we have more information in each ID, but at least it grows logarithmically in our extreme cases.

This logarithmic growth for chains is reflected in the larger-scale best-case graph, where we see long chains growing from the root.

This is kind of a lie though. The chain is logarithmic, but if we add even one more child to any node, the scheme starts to grow linearly. If our graph grows even a little in both depth and width together, we find ourselves back at the linear regime. We didn’t generate the worst-case graph above since our simulation uses a greedy search algorithm and the worst-case takes two steps to identify. The true worst-case is hard-coded and shown below, which we can see does grow linearly.

So we have yet to find an algorithm that produces logarithmic growth in all cases. Is it even possible to design a scheme that always grows logarithmically, even in the worst-case?

Unfortunately not. Here is the proof that any scheme we develop will always be linear in the worst-case.

In order to prove how fast any scheme must grow, we will look at how fast the number of possible IDs grows as nodes are added. This will require iterating over every possible assignment history and then counting how many unique possible IDs there are in the space of all possible assignment histories.

It is important to note that each path must produce a different ID. If any two paths produced the same ID, that means it would be possible to generate two nodes with the same ID.

To get our grounding, let’s first consider the tree containing all the possible 4-node paths. We will see in a moment that it will be useful to label each node using a 1-indexed Dewey system. The labels are not IDs (we are trying to write a proof about any possible ID scheme), the labels are just useful for talking about the paths and nodes.

We see every possible sequence for reaching the fourth node (only considering nodes along the path to that node) highlighted above. So we can now count how many possible IDs we need in tree with 4 nodes for any assignment order of those 4 nodes.

We see that there are 16 nodes in the tree, so whatever ID-assignment scheme we build must account for 16 unique IDs by the time we have added four nodes.

In general, notice that each time we add a new ID, we add a new leaf to every node in the tree of all possible paths. This means the number of IDs we need to account for grows as $2^{n-1}$ for $n$ nodes.

We can similarly come to this conclusion by looking at the labels. The sum of the values in a label will equal the iteration at which that node was added. It is also true the other direction: All possible paths of $n$ nodes can be generated by looking at all possible sums of numbers up to $n$, although they must be greater than 0 and the order of the sum will matter. These are known as integer compositions, and they produce the result we saw from above, $2^{n-1}$ paths for $n$ nodes.

This is an issue. Even in the ideal case where we label each possible node in the space of all histories using a counter (this is actually a valid ID-assignment scheme and generates the 2-Adic Valuation scheme we have already seen), the memory of a counter grows logarithmically. No matter what scheme we use, the memory must grow at least on the order of $\log_2(2^{n-1}) = n-1$, linearly.

Although we have proven that whatever scheme we come up with will be linear in the worst-case, it seems plausible that some algorithms perform better than others for different growth models. If we can find a reasonable growth model for humans expanding into the universe, then we should be able to reverse-engineer the best algorithm.

Space Settlement Models

Let us consider different models that approximate how humans might expand into the universe.

Small-scale

The first and easiest model to consider is random parent selection. Each time a device is added it will randomly select from all the previous devices to request an ID. This will produce what is known as a Random Recursive Tree. We will also run this at a small scale, up to around 2,048 nodes. And we will actually use the Elias omega encoding so we can have more comparable results to the Random ID assignment bit usage.

The best scheme is Binary, followed by Dewey, and Token is the worst. This makes some sense since a random tree will grow at a roughly equal rates in depth and width, which is the best-case for Binary. Dewey and Token are harder to reason about, but we suspect that Dewey does best for high-width trees and Token for high-depth trees.

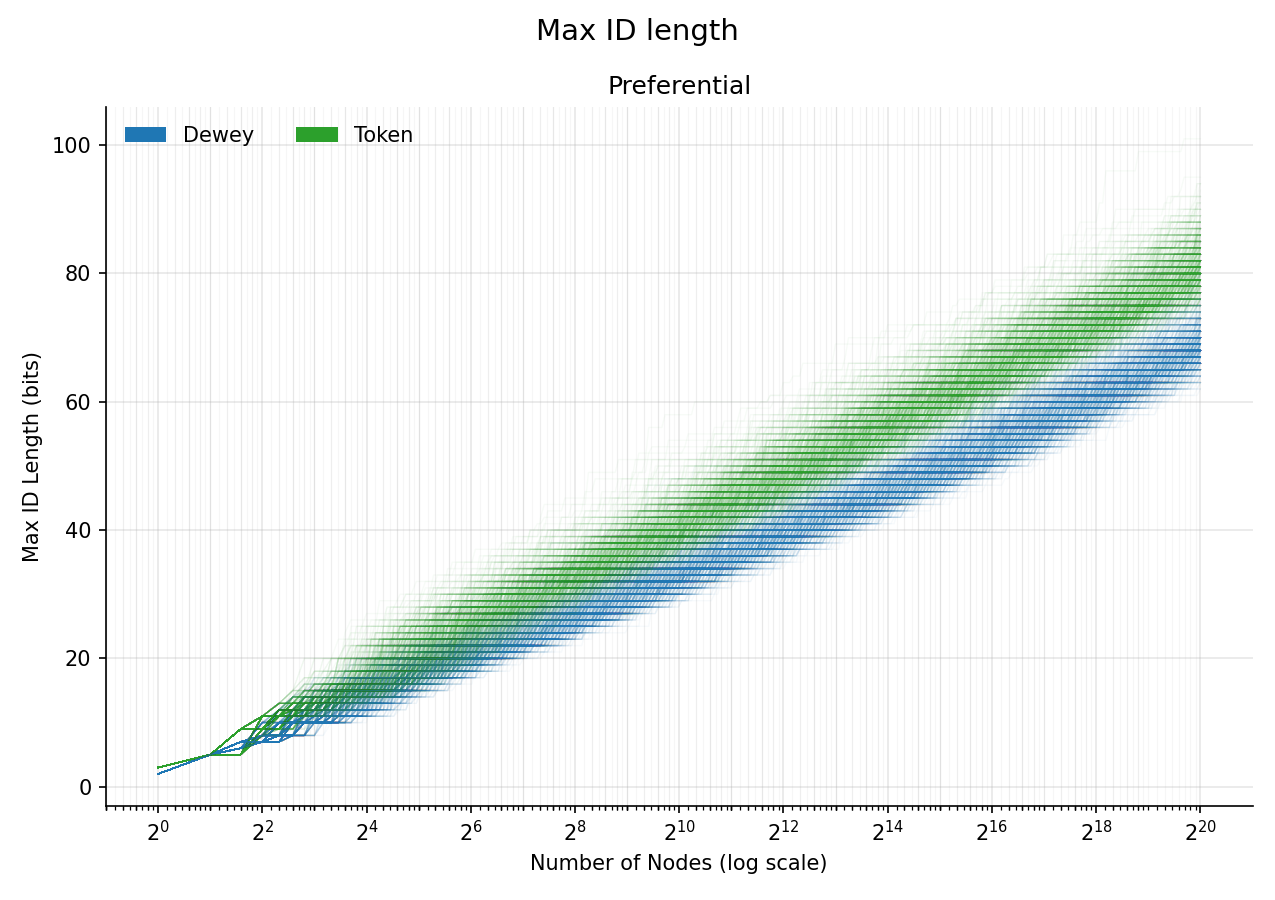

For example, we can look at a preferential attachment random graph, where nodes are more likely to connect to nodes with more connections, a model which many real-world networks follow. The width of the tree will dominate the depth, so we might expect Dewey to win out. Specifically, preferential attachment chooses a node weighted by the degree (number of edges) to choose a parent, which increases the degree of that parent, creating positive feedback. Let’s see how each ID assignment scheme handles this new growth model.

And we see that Dewey performs best, followed by Token, and then Binary by a wide margin.

Although, it seems unrealistic that devices become more popular because they assign more IDs. It seems reasonable to believe that some devices are more popular than others, but that popularity is not dependent on its history. A satellite will be very popular relative to a lightbulb, not because the satellite happened to assign more IDs in the past, but because its intrinsic properties like its position and accessibility make it easier to request IDs from. We could use a fitness model, where each node is initialized with a fitness score that determines how popular it will be. The fitness score is sampled from an exponential.

And it seems that Dewey and Binary do equally well, with Token producing the worst IDs. Although this seems pretty similar to the purely Random graph.

We need to run a large number of simulations for a large number of nodes and see if there’s a consistent pattern.

Medium-scale

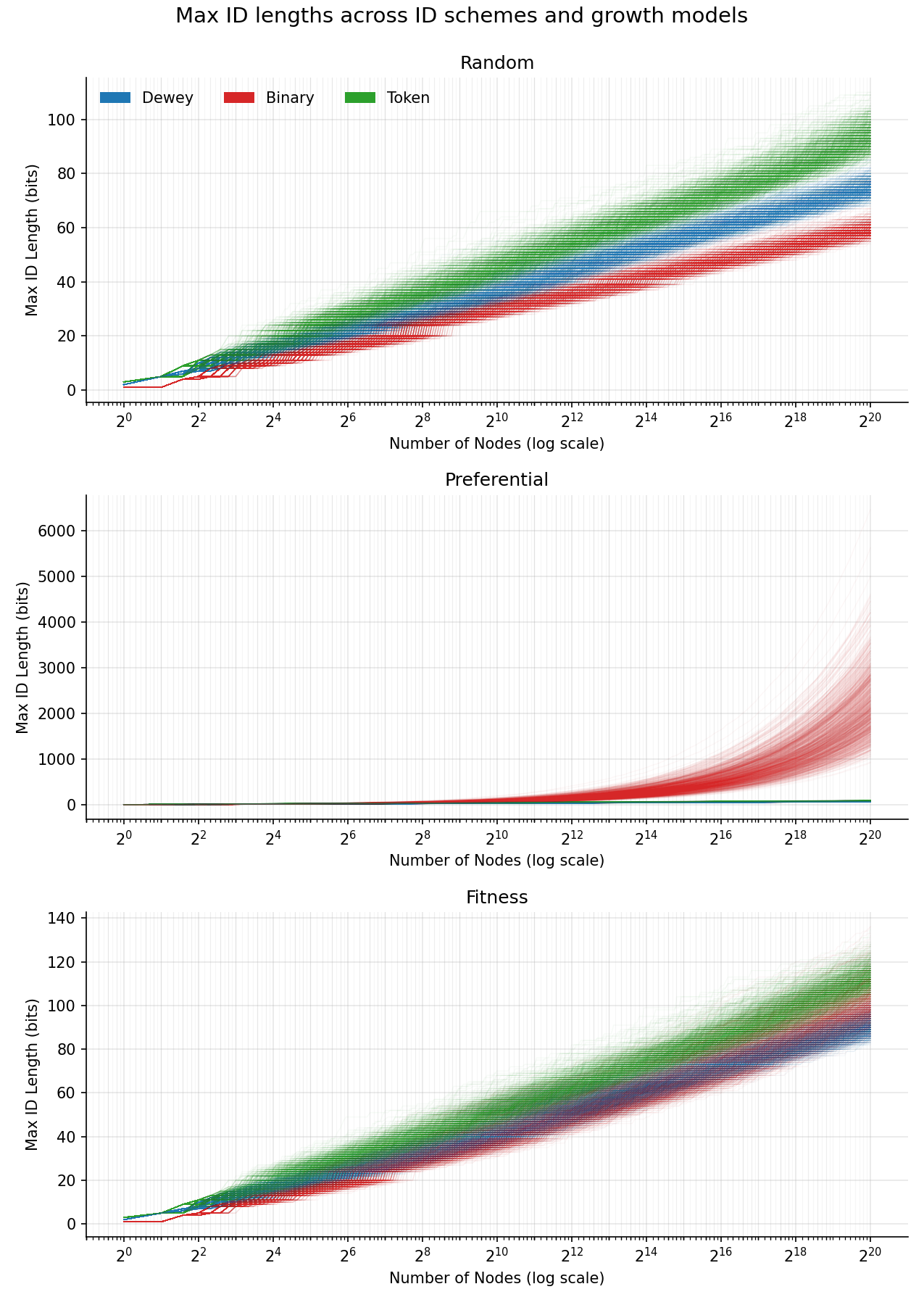

Below we run 1,000 simulations for each growth model, building a graph up to about a million ($2^{20}$) nodes. We plot the maximum ID of the graph over time. Each run is shown as a line, then the x axis is made exponential since we suspect that the IDs grow with the logarithm of the node count, which will be easier to see with an exponential x axis.

That’s some pretty clean results! We see a roughly straight line for most plots (the exceptions being Binary for the Preferential growth model and the Fitness growth model where it curves a small amount). The straight lines are a strong indication that the growth of IDs actually is logarithmic, and that we could fit a curve to it. To inspect the Preferential model for the other ID assignment schemes, let’s plot it again without Binary.

And we still see the linear trends on the exponential plot, which indicates that Dewey and Token schemes still grow logarithmically.

Here is my best explanation for why the plots are logarithmic.

In the Random growth model, each node is statistically indistinguishable from the others, so we should expect every node to see the same average subtree over time. In distribution, the subtree under the root should look similar to the subtree under the millionth node, just at a smaller scale. This suggests that we can use a recursive relation between these subtrees to infer the overall scaling law.

Suppose we simulate the growth of a 1,000-node tree and observe that the maximum ID length has increased by about 34 bits (which is what we saw for Dewey). We then take the node with the longest ID among those 1,000 nodes and conceptually re-run a 1,000-node simulation with this node acting as the root. Because the Random model treats all nodes symmetrically, we expect this node’s subtree to grow in a statistically similar way to the original root’s subtree. Since all of our ID assignment schemes have additive ID lengths along ancestry, growing this subtree to 1,000 nodes should increase the maximum ID length by roughly another 34 bits.

However, this subtree is embedded inside the full tree. By the time this node has accumulated 1,000 descendants, we should expect that all other nodes in the original tree have also accumulated, on average, about 1,000 descendants. In other words, each time we simulate an isolated 1,000-node subtree, the full tree size grows by a factor of 1,000, while the maximum ID length increases by an approximately constant amount. In practice we observed an increase closer to 38 bits rather than 34, which could be due to noise, small-(n) effects, encoding overhead, or flaws in this heuristic.

This means the ID length is growing linearly while the total number of nodes is growing exponentially. In this example, the maximum-ID-length function satisfies a recurrence of the form $T(n \cdot 1000^d) \approx T(n) + 34 d$ which is only satisfied by a logarithmic function. Writing this explicitly, we get $T(n) \propto \log(n)$ (with the base—about (1.225) in this case—set by the observed constant).

This analysis is harder to apply to the Fitness and Preferential model, as nodes are different from each other in those schemes. But the plots do indicate that it is probably still true. It might be that the analysis is still true on average for these schemes, and so the finer details about different nodes gets washed away when we scale up, but I don’t feel confident about that argument. Bigger simulations might help identify if the trends are actually non-logarithmic.

Future simulations might also consider that devices have lifetimes (nodes disappear after some time), which can dramatically alter the analysis. Initial tests with a constant lifetime (relative to how many nodes have been added) showed linear growth of IDs over time. This makes sense since it essentially forces a wide chain, which we know grows linearly for all our ID assignment schemes. Is this a reasonable assumption? What if devices live longer if they are more popular, how might that change the outcome?

For now we will use the above simulations as the first rung on our ladder of simulations, using those results to plug into larger models which then are plugged into even larger models.

Large-scale

In order to determine how many bits these schemes might require for a universe-wide humanity, we need to evaluate models of how our IDs will grow between worlds.

We will use the million-node simulation of the Fitness growth model to model the assignment of IDs on the surface of a planet for its first few years. To scale up to a full planet over hundreds of years, we can fit a logarithmic curve to our Fitness model and extrapolate.

For this analysis we will select the Dewey ID assignment scheme since it seems to perform well across all growth models.

When we fit a logarithmic curve to the max ID length of Dewey ID assignment in the Fitness growth model, it fits the curve $(6.5534 ± 0.2856) \ln(n)$ (where $0.2856$ is the standard deviation). This equation now allows us to closely approximate the max ID length after an arbitrary number of devices.

We have our model for expansion on a planet, now we need a model for how humanity spreads from one planet to the next. We can’t really know what it will look like when/if we expand into the universe, but people have definitely tried. Below are some papers modeling how humans will expand into the universe, from which we can try to create our own best-guess model more relevant to our analysis.

- Galactic Civilizations: Population Dynamics and Interstellar Diffusion, by Newman and Sagan. Essentially, expansion through the galaxy is slow because only newly settled planets contribute to further spread, and each must undergo local population growth before exporting colonists, producing a slow and constant traveling wavefront of expansion across the galaxy.

- The Fermi Paradox: An Approach Based on Percolation Theory, by Geoffrey A. Landis. Essentially, using Percolation Theory with some “reasonable” values for the rate of spreading to new planets and rates of survival, this paper finds that some wavefronts will die out while others survive, meaning we will slowly spread through the galaxy in branches.

- The Fermi Paradox and the Aurora Effect: Exo-civilization Settlement, Expansion and Steady States. Essentially, modeling solar systems as a gas and settlement as a process that depends on the distance between planets, planets living conditions, and civilization lifetimes, they find that distant clusters of the universe will fall into a steady state of being settled.

We will model the expansion between planets in a galaxy by using a constant-speed expanding wavefront that settles any habitable planet, where that new planet is seeded with a random ID from the closest settled planet. We will use the same model for the expansion between galaxies.

This will produce linear growth of ID-length as the wavefront moves outward. As each planet restarts the ID assignment process, it will cause the ID length to grow larger according to the same curve we saw for the first planet.

We have a rough estimate that there might be around 40 billion habitable planets in our Milky Way galaxy, and the latest estimates hold there are around 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe.

If we assume that planets are close to uniformly positioned in a galaxy and the galaxy is roughly spherical (many galaxies are actually disks, but it won’t change the final conclusion), then we can expect the radius of the galaxy in terms of planet-hops can be solved for using the equation of the volume of a sphere. The radius in terms of planet-hops can be approximated by $\sqrt[3]{\frac{3V}{4 \pi}} = \sqrt[3]{\frac{3 \cdot 40 \cdot 10^{9}}{4 \pi}} \approx 2121$.

If we assume each planet produces around 1 billion IDs before settling the next nearest planet, then we can calculate the ID length by the time it reaches the edge of the galaxy. This will be the amount by which the longest ID increases per planet (we are assuming 1 billion assignments) multiplied by the number of times this happens, which is the number of planets we hop to reach the edge of the galaxy. This doesn’t sound good.

\[6.5534 \cdot \ln(10^9) \cdot 2121 \approx 288048\]That is a lot of bits. And it will only get worse. We will use the same approximation for galaxies as we did for planets.

Again assuming galaxies fill space uniformly, and as a sphere, we get the number of hops between galaxies to be $\sqrt[3]{\frac{3 \cdot 2 \cdot 10^{12}}{4 \pi}} \approx 7816$. And using the $288048$ from above as the length the ID increases every galaxy, we get

\[288048 \cdot 7816 = 2251383168\]That is an exceptionally large number of bits. It would take about $281.4$ MB just to store the ID in memory.

This Deterministic solution is terrible when compared to the Random solution, which even in its most paranoid case only used 798 bits.

We might see this and try to think of solutions. Maybe we regulate that settlers must bring a few thousand of the shortest IDs they can find from their parent planet to the new planet, which would cut down the ID length per planet by around a half. But unless we find a way to grow IDs logarithmically across planets and galaxies, it won’t get you even close (remember, $2121 \cdot 7816 = 16577736$ planet hops in total).

So for now it seems the safest bet for universally unique IDs are Random numbers with a large enough range that the probabilities of collisions are functionally zero. But it was fun to consider how we might bring that probability to actually zero: designing different ID assignment schemes, running simulations, and modeling human expansion through the universe.

End

All the code for visuals, simulations, and analysis can be found at my repo on github.

This was very much an exploration with many paths left unexplored, please reach out if you explore one of them and want to chat about it, it’s good fun.

Thanks to Kevin Montambault and Jacob Hendricks for being happy to talk with me for hours on end about these strange interests of mine. I am grateful and privileged to have friends with such deep curiosities.

Side notes

Another potential interesting component of this is security. You can prevent ID-spoofing by using signatures to verify identity and that each message comes from who they claim. For the Random case, you would use your public key as your ID. For the Deterministic schemes, each node could sign their child’s public key, which would allow one to verify the chain of signatures up to the root node which all nodes have knowledge of. Replay attacks can be avoided using challenges (send and respond challenges), although they would be hard in unidirectional or delayed comms (planet to planet), so you might label messages as unconfirmed until a challenge is verified.

We should also add some error correction to the IDs so if someone for example tries to read an ID and mis-reads a letter they can correct it later. Since there are many ways to apply error correction, there should be a version number attached to the error-correcting ID.

Some objects can not store IDs themselves, such as when an ID is assigned to a planet for example, and so it’s possible that multiple IDs get accidentally assigned to the same object. In this case we should actually store a list of IDs for objects which represent all the IDs that refer to the same object.

There can be an issue related to the ship of Theseus where an object with an ID might be slowly repaired with new parts, until eventually all the parts have been replaced. Should this object still have the same ID? One pragmatic solution might be to have the ID stored in a particular piece of hardware and accept that what it means to have a particular ID is to just to have that particular piece of hardware regardless of what it is connected to.

Here are some related topics to what we have talked about in this post: Decentralized identifiers (DIDs) and Ancestry Labeling Schemes.