Fireflies

There exists a somewhat magical phenomenon in nature where a swarm of fireflies will begin flashing in synchrony.

Let’s recreate that behavior in simulation!

“Fireflies”

Starting simply, let’s have two fireflies. We assume they already know the interval to flash at (maybe it’s in their biology). Each firefly has an internal clock, and every time the clock completes a cycle, the firefly flashes. This is represented by the below code, which runs continuously. The interval represents how long we wait between flashes, and the phase tells us where in that interval we are, with phase increasing with time.

1

2

3

4

5

phase += dt;

if (phase >= interval) {

flash();

phase = 0.0;

}

We visualize the internal clocks of each firefly as a point traveling around a circle. When a fireflies clock reaches midnight (internally represented by phase >= interval), the firefly flashes.

We see these two fireflies flash at the same rate but out of phase with each other. We need a system for phase synchronization. There are many potential solutions to this problem, but we’re going to make it especially hard for ourselves. We assume a firefly has the ability to sense when a flash occurs, but nothing else. This means it doesn’t know how many fireflies there are, which firefly causes which flash, or what the internal clocks look like in other fireflies.

Phase Synchronization

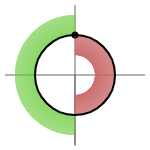

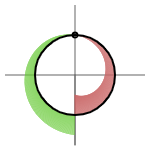

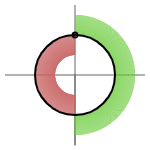

To synchronize the phase, the fireflies will follow a simple rule: If you see a flash just before you’re about to flash, flash earlier. If you see a flash just after you flashed, flash later. We’ll flash earlier by moving our phase forward a bit, and flash later by turning our phase back a bit. Here is the code and its associated graph showing the change in phase relative to when a flash is received (green means increment our phase, red means decrement, and the height tells you by how much).

1

2

3

4

5

if (phase < interval / 2) { // saw flash after, flash later

phase -= couplingConstant*interval;

} else if (phase > interval / 2) { // saw flash before, flash earlier

phase += couplingConstant*interval;

}

The circular graph is known as the phase response curve (PRC). Each time we see a firefly flash, the phase delta corresponding to where we currently are in our phase will be applied.

It sort of worked. The fireflies aren’t precisely synchronizing, their phases are jumping too far sometimes. We can fix this by having the delta depend on our phase. If a flash comes a microsecond after our flash, we don’t want to change our phase by much. The delta will be proportional to the difference between our flash and the observed flash. All together, the code is now

1

2

3

4

5

if (phase < interval / 2) { // saw flash after, flash later

phase += couplingConstant*interval*((0-phase)/(interval/2));

} else if (phase > interval / 2) { // saw flash before, flash earlier

phase += couplingConstant*interval*((interval-phase)/(interval/2));

}

This produces much cleaner synchronized phases.

This is absolutely sufficient, but for the sake of elegance I want to modify this slightly. As long as we don’t mind having a small phase delta when flashes are nearly opposite (it’ll still be an unstable point), then this can all be condensed into a sin function. This makes the code more concise and the phase response curve smooth (infinitely smooth even).

And we get synchronizing fireflies again. Let’s add some more and see how this handles multiple flashes from multiple sources. When adding more fireflies we bring down couplingConstant so visually we can see them converge more slowly.

It works! And we’ve just begun, there are many avenues to explore here: De-synchronizing phases, synchronizing frequencies, continuous models using differential equations, localized flashes rather then global ones, and the combination of all these things.

Phase De-Synchronization

Now we do the reverse. When we see a flash just before our own, flash later, and seen just after, flash earlier.

Let’s follow the same progression. The constant value phase delta for de-synchronization looks identical to the synchronizing version, but the signs are flipped.

1

2

3

4

5

if (phase < interval / 2) { // saw flash after, flash earlier

phase += couplingConstant*interval;

} else if (phase > interval / 2) { // saw flash before, flash later

phase -= couplingConstant*interval;

}

Then we may want to ignore flashes opposite from our phase while emphasizing the ones closest to us. This turns out to be very simple, just one line.

And regardless of the number of fireflies we have, they will evenly distribute themselves within the phase space (maybe applications to Time-division multiple access?).

And if we can again elegantly encode this with a sin function to get

But this removes the phase delta where it’s most critical, when fireflies flash near each other. In this particular instance the sin phase response curve is not useful.

Interval Synchronization

What if the interval is random for each firefly? This suddenly looks much more difficult. Let’s play around and see what happens anyway. First, what does a swarm of fireflies trying to synchronize phase look like with varying interval lengths?

They can’t synchronize. Even if they did synchronize for a moment, the longer interval fireflies would take longer to flash the next time, and even longer the next time.

We need an additional mechanism to update our interval. When we see a flash after our own, then perhaps our interval is too short, and so a longer interval would cause us to flash later. And the reverse for seeing a flash before our own, we need a shorter interval. We can use exactly the same code as the phase synchronization, but for interval synchronization. In fact, the only thing that changes is the sign (you can imagine if we want to flash later, that means we turn the clock back, subtracting, and we make the interval longer, adding).

1

2

phase -= couplingConstant*interval*sin(phase/interval*2*Pi);

interval += couplingConstant*interval*sin(phase/interval*2*Pi);

Later we may want to play with different coupling strengths for phase and interval synchronization, but this works well enough for now.

Or does it? If we start with slightly more varied intervals then the swarm never synchronizes. I speed up a part of the simulation below so we can see the steady state it falls into.

We notice that they fall into intervals which are multiples of each other, and that one firefly gets perpetually stuck at the beginning of its interval.

Since we ignore flashes when they’re equal or opposite our phase, fireflies can have intervals that are multiples of each other and never notice.

Phase De-Synchronization, Interval Synchronization

Because we can. Let’s combine the equations above into a model that can hopefully synchronize interval and de-synchronizes phase.

1

2

phase += couplingConstant*interval*((interval/2 - phase)/(interval/2));

interval -= couplingConstant*interval*((interval/2 - phase)/(interval/2));

And like with previous interval synchronizations, sometimes it can synchronize, sometimes not.

It is interesting to see the phases equally distribute themselves within their frequency cluster, which isn’t something I would have predicted.

Continuous Phase and Frequency Synchronization

We have been exploring the pulse based models so far, only updating our phase and frequency in response to a pulse signal (a firefly flash), but we could instead look at models that continuously update in response to the phases of other coupled oscillator. There has been extensive research in this area, and I can recommend a number of resources if you like this sort of thing. We are no longer looking at a pulse that signals other fireflies, now they get to see everyone’s clock and make continuous updates to their parameters.

The absolute go-to model in the modelling of coupled oscillators (the general name for this topic) is the Kuromoto Model. Let $\theta_i \in [0, 2\pi)$ be the phase of the $i$th coupled oscillator, $w_i$ be its frequency (we are modeling with frequency rather then the interval now, but they are just multiplicative inverses of each other), and $K$ be the coupling constant.

\[\begin{align} \frac{d\theta_i}{dt} &= w_i + \frac{K}{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} \sin(\theta_j - \theta_i) \\ \end{align}\]This looks pretty familiar! The phase delta $\frac{d\theta_i}{dt}$ is continuous now, but we should recognize this. The phase is increasing by $w_i$, then using an averaged sin phase response curve $\frac{1}{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} \sin(\theta_j - \theta_i)$ to push forward the phase when lagging behind everyone else and pushing the phase backward when leading too far in front.

Running this equation on fireflies with equal frequencies, we get a familiar sight (but remember, the flash is just for show now, it doesn’t mean anything to the model anymore).

And this model doesn’t do too bad generalizing to varying frequencies $w_i$.

As long as the coupling constant $K$ is large enough, the oscillators will become “phase locked”. This means they will all be moving at the same frequency but with a constant value separating the phases. If you stare at the Kuromoto Model for long enough this will make good sense.

I’m a bit bothered by the phases failing to perfectly synchronize, so let’s fix that. Inspired by our pulse based frequency synchronization, let’s modify the Kuromoto Model slightly. We add the ability for the natural frequencies $w_i$ to change over time. Just like before, the frequency follows exactly the same equation as the phase (although not constantly increasing, so no leading term). I’ll also introduce a frequency coupling constant $L$.

\[\begin{align} \frac{d\theta_i}{dt} &= w_i + \frac{K}{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} \sin(\theta_j - \theta_i) \\ \frac{dw_i}{dt} &= \frac{L}{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} \sin(\theta_j - \theta_i) \end{align}\]Running these equations to steady state can take some time, but they look pretty along the way, so here’s an interactive simulation that can be reset and put in fast forward.

You can see an analysis of these equations in an even more general setting where noise is considered in this paper.

Continuous Phase De-synchronization

We start with constant frequency across the fireflies.

Just like in the pulse based model, we want to use the proportional phase response curve rather then the sin phase response curve. Again, this is because what we care about in de-synchronizing is moving farther form the phase nearest to us, which the sin phase response curve ignores. We can naturally move our pulse based model equations into the continuous setting to get

\[\begin{align} \frac{d\theta_i}{dt} &= w_i + \frac{K}{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} P(\theta_j, \theta_i) \\ \end{align}\]where

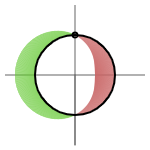

\[\begin{align} P(\theta_a, \theta_b) = \begin{cases} 0 & \theta_a = \theta_b \\ \frac{\theta_b - \theta_a \bmod 2\pi}{\pi} - 1 & \theta_a \ne \theta_b \end{cases} \end{align}\]Which we might recall is this phase response curve. The top dot now represents the position of $\theta_b$, so if we ($\theta_a$) are ahead, we will speed up, and if we are behind, we slow down.

And we get

And now we add varying frequencies. Like before, we use the same phase response curve for the frequency response curve, so our equations can be written as

\[\begin{align} \frac{d\theta_i}{dt} &= w_i + \frac{K}{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} P(\theta_j, \theta_i) \\ \frac{dw_i}{dt} &= \frac{L}{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} P(\theta_j, \theta_i) \\ \end{align}\]With the same $P(\theta_a, \theta_b)$ as before.

And again, we see varying frequencies can synchronize frequency with de-synchronizing phase, but only if the frequencies start out similar to each other.

Future investigation

Something that I plan on exploring later is localized flashes, where each flash is only seen by other nearby fireflies. This can lead to waves of light traveling across the fireflies, or rings of fireflies that can never synchronize. For a really fantastic introduction to synchronicity and an overview of recent work leading up to these swarms that never synchronize, check out this lecture by Steven Strogatz speaking at the Sante Fe Institute.

You can check out the code used to generate the graphics for this blog post here.