Concept

Imagine you have a secret that you want to distribute among some friends, but no individual should know the secret, they must all come together to re-create the secret. How might we do this?

Algorithm attempt 1

Let’s say the secret is the number 3214 and you have four friends. One idea is to give each friend a different digit in the number. Then one person would get (0,3), which tells them the 0th digit is 3. Another friend gets (2,1), and when the two friends come together they know the secret looks something like 3_1_. This secret-sharing algorithm has some issues though. If three of the four friends come together, they are very close to knowing the secret and may be able to brute-force/guess the final digit, which we don’t want. We also run into an issue if we have more friends than digits since we can’t give everyone a unique digit.

Algorithm attempt 2

Perhaps the next solution is to give everyone a random number such that the sum of all these numbers is your secret. So for the secret 3214 and four friends, the parts of the secret (called shares) might look like 5, 1022, 40, and 2147. This algorithm is independent of the number of friends we have, which solves one of our problems. But there is still the issue that as more friends come together they get closer to discovering our secret since they know the lower bound.

Algorithm attempt 3

We will still use the random numbers that sum to our secret, but this time we’ll do it modulo some number. This means if we use modulo $10000$, then our shares could look like 3566, 20, 9831, and 9797 (since $(3566+20+983+9797)\%10000 = 3214$). Now when three of the four friends come together they have no clue what the secret might be, they don’t even have a lower bound.

This satisfies all the properties we wanted up to this point, but our secret holder decides there’s a new property they want. Our secret holder wants the secret to be re-created if any two of his four friends come together (how many people must come together to create the secret is called the threshold, in this case, the threshold is two). All the previous algorithms do not work within these new requirements, so let’s think up some new algorithms.

Algorithm attempt 4

Perhaps if we give everyone most of the secret, but each person is missing a unique piece. Example shares could look like 3_14, _214, 32_4, and 321_. Now when any two people come together they can recreate the secret. This satisfies our new property, but has all the issues from before: the solution can be brute forced, and you’re secret must be split-able among the number of friends you have.

Although this algorithm is not what we are looking for, it’s still interesting to consider how you might adapt it for different thresholds.

It is easiest to simplify the problem by handing out bit masks of the secret, so if we consider the share 0110, then the person would have the second and third digits of the secret. When multiple shares are brought together, you simply OR the bitmasks to check if you get all 1s, which would mean you have uncovered the entire secret. How do we generate the bit masks such that when N (the threshold) people come together they get all 1s, but when $N-1$ people come together there will always be a 0 left? It’s not immediately obvious that this is even possible outside of the trivial cases.

The trivial cases are a threshold of everyone and a threshold of 2. For everyone, you just hand out a different digit to each person, that way all people need to come together to have all the digits. For $N=2$, everyone has the entire secret, except a single digit, unique to each individual. Now when anyone comes together they will be missing different digits and can exchange them with one another to complete the secret.

The next simplest case is a threshold of 3 among 4 people. This problem is fun to consider on your own, so take a moment before looking at the solution below. Verify that any two masks will always leave out some of the secret, but any three will always complete it.

1

2

3

4

000111

011001

101010

110100

This can be generalized to any threshold $N$ and any number of people $K$. You generate the masks by enumerating all combinations of $N-1$ 0s along the columns of the masks (so start with $N-1$ zeros and $K-N+1$ 1s, then add a new column for each new enumeration until all combinations are exhausted). The resulting rows are the masks.

Since there are at most $N-1$ 0s in a column, this construction ensures that there can not exist any combination of $N$ masks that will be missing a digit. But how does this ensure that there will always be a digit missing for any $N-1$ combinations of masks? Consider for a moment, sometimes an example can help, below is $N=3$ and $K=6$.

1

2

3

4

5

6

000001111111111

011110000111111

101110111000111

110111011011001

111011101101010

111101110110100

Because we made sure to exhaust all enumerations of $N-1$ 0s in the columns, then for any $N-1$ masks we bring together, one of their columns must contain all zeros, for that is an enumeration (if we look at the remaining masks, they will all have 1s in that same column).

Here’s a one-liner in Python to generate the N threshold masks for $K$ people.

1

print('\n'.join(map(''.join, zip(*[[str(1-(j in c)) for j in range(K)] for c in combinations(range(K), N-1)]))))

And now for the very clever solution developed by Adi Shamir.

Shamir’s Secret Sharing Algorithm

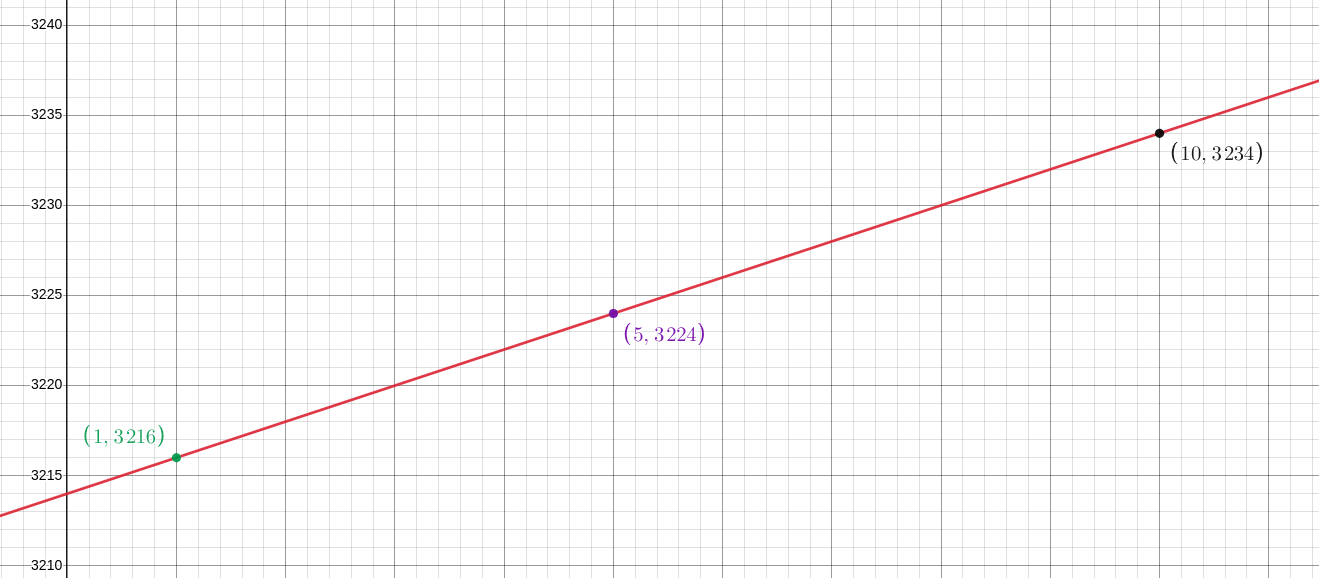

To introduce the core concept, let’s start with the most basic example. You want a threshold of 2 for the secret 3214. We encode that secret in a line, which can be done a number of ways, let’s encode it as the y-intercept. The slope we pick at random, say 2, so we get the line $y=3214+2x$. Now we can hand out points on the line (the shares) to our friends. If any two of our friends come together they can recreate the line and discover our secret. For example, you hand out points on the line (1, 3216), (5, 3224), and (10, 3234).

So if (5, 3224), and (10, 3234) are brought together we can recover the secret $b$ by plugging one of the points into $y=(3234-3224)/(10-5)*x+b$ to solve for $b$.

Note that we can hand out as many shares as we want, even handing out shares at a later date (being mindful not to hand out the same point twice), so there is no dependency on the number of friends we have.

For larger thresholds, we use the general fact that N points uniquely define a $N-1$ degree polynomial. So for a threshold of $N$, we take our secret and encode it in a $N-1$ degree polynomial.

It turns out this is not perfectly secure since when $N-1$ people come together they can solve for a finite range that the secret must exist in. An example is a bit complicated, but the solution is not. We again use a modulus for our polynomials, which makes the algorithm secure (and the code easier). By picking a modulus that is prime we create what is known as a field, allowing for division to be defined, which will be necessary to solve our system of equations.

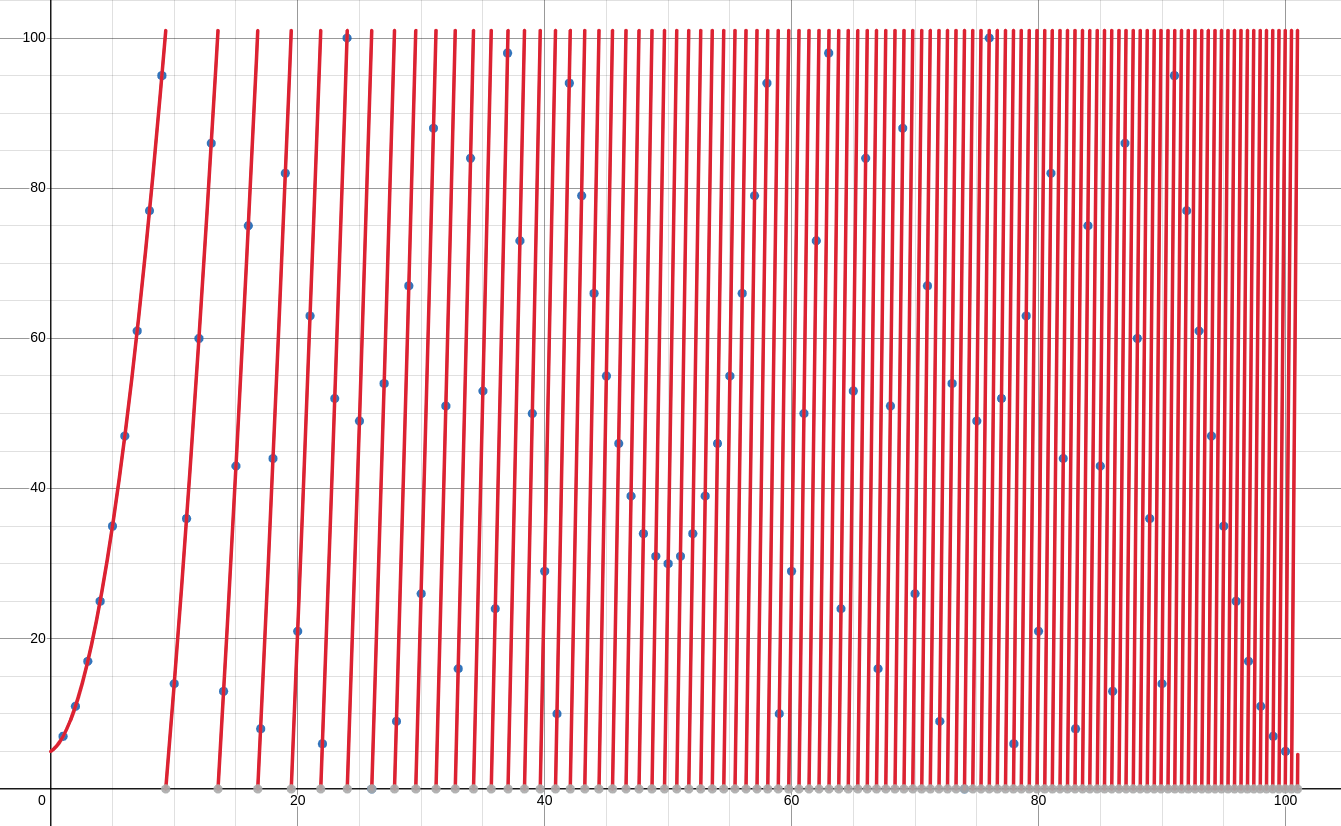

Below we see intuitively how taking the modulus makes predictions difficult. We see all the integer points on the polynomial $5+x+x^2 \% 101$. Given any of the 2 blue points, nothing can be said about the underlying polynomial.

Now that we are doing operations on polynomials we are able to do Secure Multi-party Computation. This means lots of people can have a secret, and everyone can get the sum of everyone’s secret without ever learning anyone’s secret. But it’s not just summing, it turns out that once you define AND, NOT, and OR (or just NAND) on polynomials it becomes Turing complete and everyone can calculate arbitrary functions on inputs that are secret. This is how the Danish Sugar Beet Auction was run.

Code

The first thing we need are operations in the modulus space we are working with. This is a bit tricky since we are actually already in a modulus space due to computers having limited space for each number. Below we see the new basic math operations that handle overflow in a modulus space.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

func add64Mod(left, right, prime uint64) uint64 {

if left > math.MaxUint64-right { // overflow

diff := (math.MaxUint64 % prime) + 1

return add64Mod(left+right, diff, prime)

}

return (left + right) % prime

}

func sub64Mod(left, right, prime uint64) uint64 {

return add64Mod(left, neg64Mod(right, prime), prime)

}

func neg64Mod(n, prime uint64) uint64 {

return prime - (n % prime)

}

// https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/how-to-avoid-overflow-in-modular-multiplication/

func mult64Mod(left, right, prime uint64) uint64 {

left %= prime

right %= prime

var res uint64 = 0 // Initialize result

for right > 0 {

if right%2 == 1 {

res = add64Mod(res, left, prime)

}

// Multiply 'left' with 2

left = add64Mod(left, left, prime)

right /= 2

}

return res

}

func div64Mod(left, right, prime uint64) uint64 {

left %= prime

right %= prime

if right == 0 { // cannot divide by 0

fmt.Println("cannot divide by zero")

return 0

}

return mult64Mod(left, inverse64Mod(right, prime), prime)

}

// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extended_Euclidean_algorithm

func inverse64Mod(n, prime uint64) uint64 {

n %= prime

var old_r, r uint64 = n, prime

var old_s, s uint64 = 1, 0

// var old_t, t uint64 = 0, 1

for r != 0 {

quotient := old_r / r

old_r, r = r, sub64Mod(old_r, mult64Mod(quotient, r, prime), prime)

old_s, s = s, sub64Mod(old_s, mult64Mod(quotient, s, prime), prime)

// old_t, t = t, sub64Mod(old_t, quotient*t, prime)

}

// Bézout coefficients: (old_s, old_t)

// greatest common divisor: old_r

// quotients by the gcd: (t, s)

return old_s

}

Now we need a polynomial defined using these math operations. We need to be able to generate points from polynomials (generating shares), and polynomials from points (recovering the secret). This requires some basic operations on polynomials which we will skip (it’s boring and long, but a link to the repo is at the end of the article if you want to see it). Note that these are not the secure multi-party computation functions, those would need to look slightly different to ensure the secret is kept invariant.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

type Share struct {

X, Y uint64

}

type PolynomialField struct {

coefficients []uint64

prime uint64

}

func (polynomial1 PolynomialField) add(polynomial2 PolynomialField) PolynomialField {

...

}

func (polynomial1 PolynomialField) sub(polynomial2 PolynomialField) PolynomialField {

...

}

func (polynomial1 PolynomialField) mult(polynomial2 PolynomialField) PolynomialField {

...

}

func (polynomial PolynomialField) scale(s uint64) PolynomialField {

...

}

To generate points we simply need an evaluation function, and to generate polynomials we use Lagrange interpolation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

func (polynomial PolynomialField) eval(x uint64) Share {

// Horner's method

degree := len(polynomial.coefficients) - 1

y := polynomial.coefficients[degree]

for i := degree - 1; i >= 0; i-- {

y = add64Mod(mult64Mod(y, x, polynomial.prime), polynomial.coefficients[i], polynomial.prime)

}

return Share{x, y}

}

func lagrangeInterpolate(points []Share, prime uint64) PolynomialField {

n := len(points)

sum := PolynomialField{make([]uint64, 0), prime}

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

product := PolynomialField{[]uint64{1}, prime}

for j := 0; j < n; j++ {

if j == i {

continue

}

frac := PolynomialField{[]uint64{sub64Mod(0, points[j].X, prime), 1}, prime}

frac = frac.scale(inverse64Mod(sub64Mod(points[i].X, points[j].X, prime), prime))

product = product.mult(frac)

}

product = product.scale(points[i].Y)

sum = sum.add(product)

}

return sum

}

However, there turns out to be a more computationally efficient algorithm to generate the y-intercept given the points on the polynomial.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

func lagrangeInterpolateEval(points []Share, x, prime uint64) Share {

n := len(points)

var sum uint64 = 0

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

var product uint64 = 1

for j := 0; j < n; j++ {

if j == i {

continue

}

product = mult64Mod(

product,

div64Mod(

sub64Mod(x, points[j].X, prime),

sub64Mod(points[i].X, points[j].X, prime),

prime),

prime)

}

sum = add64Mod(

sum,

mult64Mod(product, points[i].Y, prime),

prime)

}

return Share{x, sum}

}

And now to place a simple API on top of these polynomials we can create a Secret Sharing library. Note that here we encode the secret in the coefficients of the polynomials, which means for very large secrets you need higher degree polynomials (each coefficient can only store so much of the secret), but you can maintain the threshold by handing out more shares to each individual.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

// this large prime lets us encode information into the first 63 bits of uint64

var prime uint64 = 18446744073709551557

type SecretSharing struct {

polynomial PolynomialField

counter uint

}

func NewSecretSharing(secret []byte, requiredShareCount int) (SecretSharing, error) {

poly, err := encodeSecret(secret, uint(requiredShareCount))

if err != nil {

return SecretSharing{}, err

}

return SecretSharing{

polynomial: poly,

counter: 1,

}, nil

}

func (s *SecretSharing) GenerateShare() Share {

share := s.polynomial.eval(uint64(s.counter))

s.counter++

return share

}

func (s *SecretSharing) GenerateShareAt(x int) Share {

return s.polynomial.eval(uint64(x))

}

func encodeSecret(bytes []byte, requiredShareCount uint) (PolynomialField, error) {

// well just use every 7 bytes since it will fit in our encoding, although it's not as storage efficient as it could be

neededCoefficients := uint(len(bytes)-1)/7 + 1

if neededCoefficients > requiredShareCount {

return PolynomialField{}, fmt.Errorf("Secret needs more space to be encoded, need at least %d coefficients\n", neededCoefficients)

}

coefficients := make([]uint64, requiredShareCount)

// first fill the coefficients with non-zero values, then we will overwrite with our own

for i := uint(0); i < requiredShareCount; i++ {

coefficients[i] = 1

}

for i := uint(0); i < neededCoefficients-1; i++ {

formatted := make([]byte, 8)

copy(formatted, bytes[7*i:7*(i+1)])

coefficients[i] = binary.LittleEndian.Uint64(formatted)

}

// there may be some bytes left over

formatted := make([]byte, 8)

copy(formatted, bytes[(neededCoefficients-1)*7:])

coefficients[neededCoefficients-1] = binary.LittleEndian.Uint64(formatted)

return PolynomialField{coefficients, prime}, nil

}

func DecodeSecret(shares []Share, degree int) ([]byte, error) {

// make sure the provided information is valid

if len(shares) < degree {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("not enough shares to decode")

}

for i, share1 := range shares {

for j, share2 := range shares {

if i == j {

continue

}

if share1.X == share2.X {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("shares must be distinct")

}

}

}

decodedPolynomial := lagrangeInterpolate(shares[:degree], prime)

bytes := make([]byte, 0)

for _, coefficient := range decodedPolynomial.coefficients {

b := make([]byte, 8)

binary.LittleEndian.PutUint64(b, coefficient)

bytes = append(bytes, b[:7]...)

}

return bytes, nil

}

Below is an example using the Secret Sharing library, and following that is an example of a secure multi-party computation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

requiredShares := 6

ss, err := shamir.NewSecretSharing([]byte("this is my secret"), requiredShares)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

// distribute these shares to people, then when they gather together they will have this array

shares := make([]shamir.Share, requiredShares+2)

for i := 0; i < len(shares); i++ {

shares[i] = ss.GenerateShare()

}

decoded, err := shamir.DecodeSecret(shares, requiredShares)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

// note that the secret is in decoded, but will be padded, so decoded is not exactly the secret

fmt.Println(decoded)

fmt.Println(string(decoded))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

// we will store the secret in the first byte

requiredShares := 3

// person 1 will generate final point at x = 1, so distributes shares at 2 and 3

s1 := []byte{byte(7)}

p1, _ := shamir.NewSecretSharing(s1, requiredShares)

share1a := p1.GenerateShareAt(2)

share1b := p1.GenerateShareAt(3)

s2 := []byte{byte(9)}

p2, _ := shamir.NewSecretSharing(s2, requiredShares)

share2a := p2.GenerateShareAt(1)

share2b := p2.GenerateShareAt(3)

s3 := []byte{byte(1)}

p3, _ := shamir.NewSecretSharing(s3, requiredShares)

share3a := p3.GenerateShareAt(1)

share3b := p3.GenerateShareAt(2)

// the generated shares (share(number)(letter)) should be sent securely to each other

// person 1 generates their share of the final sum

shareSum1 := shamir.Share{X: 1, Y: p1.GenerateShareAt(1).Y + share2a.Y + share3a.Y}

shareSum2 := shamir.Share{X: 2, Y: share1a.Y + p2.GenerateShareAt(2).Y + share3b.Y}

shareSum3 := shamir.Share{X: 3, Y: share1b.Y + share2b.Y + p3.GenerateShareAt(3).Y}

// the shares should then be sent securely to each other

decoded, err := shamir.DecodeSecret([]shamir.Share{shareSum1, shareSum2, shareSum3}, requiredShares)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

fmt.Println(decoded)

fmt.Println(int(decoded[0]))

The full repo can be found here.

While I have shown you the sum operation for secure multi-party computation, multiplication is more difficult, but if you want to calculate arbitrary functions for secure multi-party computation, it will be necessary.

Now you can share secrets that require a threshold of people to recreate, which has many applications. A fun one to try is to “store” a password across multiple devices, where each device has a share of the password. If you have 8 devices, then perhaps use a threshold of 6 (devices can break sometimes), and whenever you want the password you query each device. This means you no longer have a single point of failure for your passwords. Someone would have to either break in by hacking 5 of your 8 devices or launch a denial of service attack by disabling 3 of your 8 devices. This is a lot better than a single device that can be hacked or broken.