What would it look like to walk in a universe where geometry is broken? We will be able to bend space, shrink it, and connect it in strange ways. First, let’s discover that non-euclidean universes are already familiar to us, then let us create a way to represent new universes, and finally, let’s walk in these strange places.

Familiar Non-Euclidean Geometry

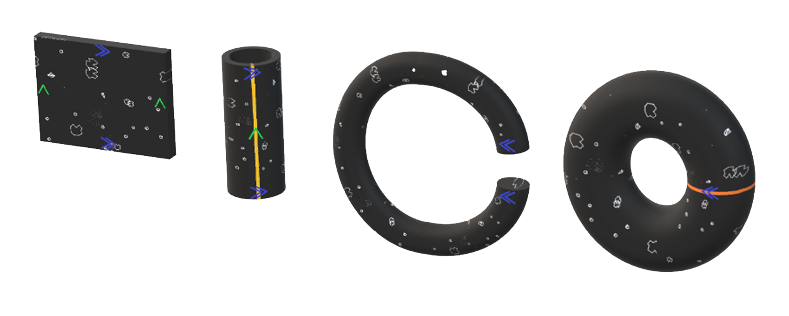

If you have ever played an old arcade game where you go off one side of the screen and appear on the other, then you’ve already walked in non-euclidean universes. If we look at Pac-Man, he can walk from one side of the screen to the other, then keep walking off the screen to reappear back where he started. You are playing Pac-Man on a cylinder.

Or if you look at Asteroids, where you can go off the top of the screen to appear on the bottom, or off the left to appear on the right, this is a torus (doughnut).

But it’s not just games, our universe is non-Euclidean! It turns out that mass bends space and time itself (but let’s just focus on the space bit), so that with large enough masses we can create gravitational lenses, or detect the collision of black holes by measuring the bending of space from the resulting gravitational waves.

There are many ways of breaking Euclid’s rules which describe our familiar geometry, and yet they still work. But perhaps we can bend the rules even further? We will develop a method for describing our own universes that can contain bent space, reconnecting bits, holes, and more.

The fabric of our universes

While it would be nice to model the universe mathematically, this would make taking pictures within it very difficult (lots and lots of differential geometry to calculate geodesics on our arbitrarily defined universe). Instead, we will approximate the universe as lots of nodes and edges. Imagine the world around you is actually just a really fine grid where all the elementary particles jump from one node to the next over tiny time steps. This would be similar to looking at the GIF with the white sphere above and thinking that you see a perfect circle smoothly orbiting another perfect sphere. Of course, we know if you look close enough it’s just square pixels that change multiple times a second. Perhaps if you could look closely enough at our universe we’d find it’s a graph? Probably not, but who knows?

It’s good enough for us. Let’s start with the most basic universe to get introduced to this representation. A flat grid of nodes that connect at 90 degrees to their neighbors. Then we want a particle to have some velocity and move through this space.

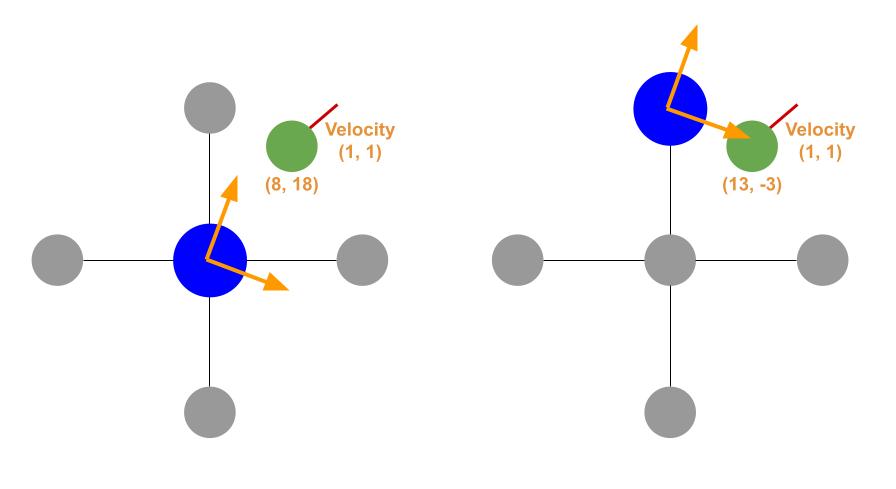

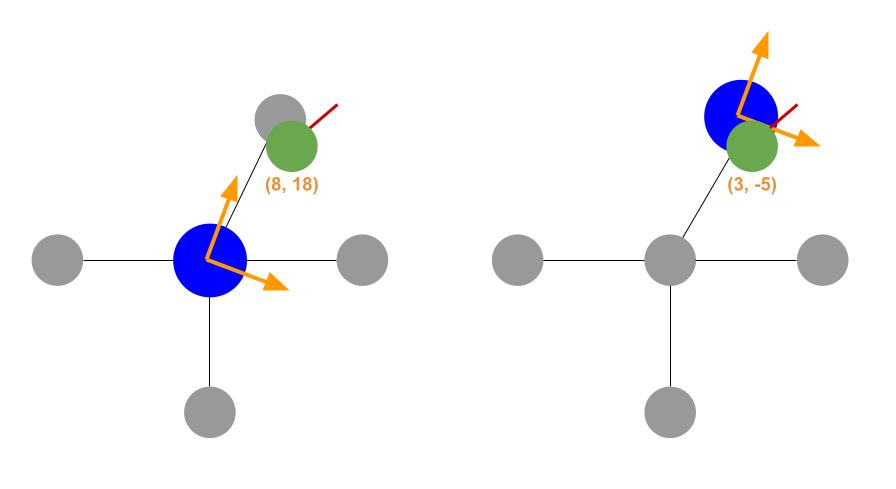

Let’s walk through what’s happening here. The blue circle is our particle, hopping from one node to the next over time. In order to travel in a “straight line” the particle keeps track of its desired position (green circle) and velocity (arrow out of green circle) and jumps from one node to the next trying to stay as close to the desired position as possible. But we have to be very careful in how we represent this desired position. We could store it as (x,y) relative to some “origin”, but this concept of an origin is very Euclidean, it won’t fit well in our future universes. Instead, we store the desired position relative to the particle’s current “position”, where I put position in quotations because again we can’t assign a coordinate to our particle. The particle will have its own reference frame that the desired position will use as the origin for its coordinates. When the particle hops from one node to another, we update the desired position.

An example would be helpful.

We see from the first frame to the next that the relative position of the desired position changes due to the blue ball moving from one node to another. You can then see from the GIF that for many following frames the blue ball stays still (since there are no edges which traveling across would bring closer to the desired) while the green ball moves according to its velocity. How we specifically transformed the green ball depends on the direction and distance of the outgoing edge we traveled across. If the outgoing edge had been a different transform, the green ball would have different coordinates in the second frame, like below

With this, we have a particle that can travel in a “straight line” across our graph. And now we can start breaking the rules.

New Rules

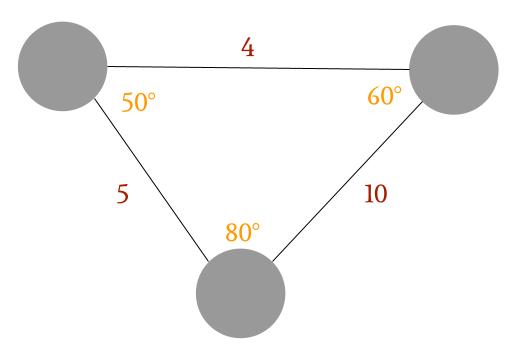

A fact known by school children is that all triangles have angles that sum to 180 degrees, no matter the kind of triangle you have. But since we define the outgoing transforms at each node independently from each other, there exists no such restriction. You can then construct triangles with any sum of angles. Below the angle sum is 190 degrees, and the edges violate the triangle inequality.

Although these rules were broken, that doesn’t stop a particle from being capable of moving across the graphs according to the rules for movement we created.

Because our universes are defined as edges and nodes where we can define the transforms for each node independently, we can also connect nodes that would usually be far away. For example, we can now recreate the cylindrical universe from Pac-Man. We make a grid of nodes and connect them in the normal Euclidean way, except we also connect the left and right edge nodes to each other.

And we have our first non-Euclidean world! But, what does it look like to walk around this universe? Since we launch particles in straight lines, we can also do raycasting! First, we need a person though, so we will have a “camera” particle, whose desired position is controlled by our key presses. Then for each column of pixels on the screen, we will shoot out a “ray” particle, which travels in a straight line until it hits something. Based on the distance and color of the object hit, we can draw pixels to the screen to show the player that an object is ahead. This is also a trick used for the first-ever “3D” game, which wasn’t actually 3D, but used this trick.

Now let’s see a character moving around our cylindrical universe, then see the world from their perspective.

From the first-person perspective, we see a world that seems endless along one of its axes, but we know from our construction that it’s actually a universe that connects to itself and is very finite. We also see blue things that seem to follow us at a set distance on either side of us. If we had a more detailed renderer we would actually find that we are seeing the back of ourselves. Since the universe wraps itself from left to right, if we look straight ahead we see our backs.

How about a torus, like in Asteroids?

We see a repeated universe in all directions, an infinite (single?) number of ourselves. You may also notice the graph representation was also a torus rather than the grid we’ve been using, but don’t let that fool you. The graph cannot be embedded in Euclidean space (that’s why we made them), so we can never truly represent them on screen. But we can make really helpful approximations that give us an intuitive understanding of the shape of the universe we walk in. Let’s look at slightly less intuitive shapes to walk in.

The following are the Mobius strip, the Klein Bottle, and the Sphere.

For the sphere, you should actually see your face around the universe at a distance equal to the circumference of the universe. Because this is an approximation, some of the raycasting misses our body and travels around the sphere again. Try to image the 3D equivalent of a spherical universe. Looking up you would see the soles of your feet, to your left your right, to your front your back. With nothing else to block your view, you would see an unbroken image of yourself wrapped around the universe.

And now let’s look at a flat space with a large bump in the middle. This is similar to the images you get when looking up general relativity. This is our equivalent of gravitational lensing, although we simply placed the bump there, no mass is needed (it’s a better view without it).

Note that although there are only 4 walls, the lensing makes it look like there are many more. If it isn’t already clear (as if), this isn’t just a trick of the light, the universe itself is bent. The light is still traveling along straight lines, but straight lines in a bent universe. You can now see why even the mass-less photon gets bent by a black hole, they are traveling through a bent area of space.

And finally, let’s make a Tardis, a box that’s bigger on the inside.

Although perhaps we shouldn’t call it “inside”. If you look closely, it’s more like a solid box with a door to an orthogonal universe, or perhaps a pocket universe connected to the door. Again, the 3D representation is just there to help us, it can’t truly represent the universe we build.

With this graph representation, we can create some truly wild universes, only a few of which you saw here. Add a fairly functional rule for “straight lines” and we get to walk around and view these universes from the inside.

While fascinating in 2D, what more could you do in 3D? You could build a world for VR where there are pockets of pockets of pockets of universes, and the last brings you back to the first. A short tunnel that carries you across continents, and a patch of grass that takes years to cross. A room where if you travel too far forward you end up back where you started, but turned 90 degrees. A hallway with no correct label for left or right, for if you walk forward you end up back where you started, but now everything is mirrored (we did this with the Mobius strip).