Roundless

Currently the economy uses buy/sell rounds in order to match up buyers and sellers, but this won’t work in our final simulation. A simulated RPG economy will have buyers that somewhat randomly search out shops to buy desired goods, usually with large spaced out time intervals. This means sellers will receive buyers at random points in time and sporadically. How might a seller determine if they have too few customers because of high prices or because buyers just aren’t interested at that moment?

For now lets use the simple solution that after a threshold number of failures to transact, an actor makes a better offer. Below we implement what we have mentioned (full repository link at end of article)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

// usually people don't try to buy or sell things

if rand.Float64() > 0.1 {

return

}

actor.timeSinceLastTransaction++

// only buyers initiate transactions (usually buyers come to sellers, not the other way around)

if actor.isBuyer() {

// look for a seller, simulates going from shop to shop

for otherActor := range actors { // randomly iterates through everyone

if !otherActor.isSeller() {

continue

}

// seller is asking for too high a price, move to the next one

if actor.expectedMarketValue < otherActor.expectedMarketValue {

continue

}

// passed all checks, transacting

actor.timeSinceLastTransaction, otherActor.timeSinceLastTransaction = 0, 0

actor.expectedMarketValue -= actor.beliefVolatility

otherActor.expectedMarketValue += actor.beliefVolatility

break

}

}

// if we haven't transacted in a while, update expected values

if actor.timeSinceLastTransaction > actor.maxTimeSinceLastTransaction {

actor.timeSinceLastTransaction = 0

if actor.isBuyer() {

// need to be willing to pay more

actor.expectedMarketValue += actor.beliefVolatility

} else if actor.isSeller() {

// need to be willing to sell for lower

actor.expectedMarketValue -= actor.beliefVolatility

}

}

And we can see below that we get roughly the same behavior as before, but now the simulation is untethered from rounds (but this solution is not totally general, a more intelligent solution would determine how to update beliefs based on more factors). Note that the below is actually running 100 iterations per frame, this is because people are much slower to buy/sell now, so the simulation needs to be sped up.

Scarcity

Currently actors don’t actually trade anything, they essentially walk around asking “Would you sell this item for this amount of money? No? How about this much? Yes? Good to know.” and they continue on. Lets give each actor some number of goods and money, which they will give and take during a transaction. We need to start being careful now, enough ideas are interacting with each other that we could easily miss a conceptual bug.

An easy bug we could miss is continuing to just wait for enough time to pass without a transaction in order to update our market beliefs. Instead, we should wait for enough time to pass without a transaction where we could have transacted, but didn’t. This means if we want to buy something but don’t have the money, we shouldn’t consider that time towards updating our market beliefs. That would be like a person thinking “I wasn’t able to buy a car since I didn’t have enough money, but next time I’ll offer more money and be sure to get it.” This is obviously nonsense, but it can be easy to miss in code.

Below is the implementation of limited goods and all the checks needed to make a transaction

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

// only track failed time for when we could transact but didn't

if actor.isBuyer() && actor.money > actor.expectedMarketValue {

actor.timeSinceLastTransaction++

} else if actor.isSeller() && actor.goodCount > 0 {

actor.timeSinceLastTransaction++

}

// only buyers initiate transactions (usually buyers come to sellers, not the other way around)

if actor.isBuyer() && actor.money >= actor.expectedMarketValue {

willingBuyPrice := actor.expectedMarketValue

// look for a seller, simulates going from shop to shop

for otherActor := range actors { // randomly iterates through everyone

if !otherActor.isSeller() || otherActor.goodCount == 0 { // must be a seller with goods to sell

continue

}

sellingPrice := otherActor.expectedMarketValue // looking at the price tag

if willingBuyPrice < sellingPrice || actor.money < sellingPrice { // the buyer is unwilling or unable to buy at this price

continue

}

// passed all checks, transacting

actor.money -= sellingPrice

otherActor.money += sellingPrice

actor.goodCount++

otherActor.goodCount--

actor.timeSinceLastTransaction, otherActor.timeSinceLastTransaction = 0, 0

actor.expectedMarketValue -= actor.beliefVolatility

otherActor.expectedMarketValue += actor.beliefVolatility

break

}

}

But when we run the code, our actors no longer converge to a market price, why? If we also plot the number of goods a person has against the amount of money they have, we quickly see the reason.

Very quickly people either sell all their goods for money or give all their money in exchange for goods. This stops people from buying or selling and the whole market freezes, no more market signals or updates. If we consider these actors which simply want to maximize utility, then of course they will exchange all of their money for something more valuable (to them), even to the point of ruin. What stops real people from behaving this way? One factor is diminishing utility (it’s much more, but this will be sufficient for now). Although initially the good you bought may be worth \$10, once you have that good, the next will be worth less to you, maybe \$8. We need to define a graph for the personal value of a good versus the number of goods owned.

We won’t use state, click here to see why, but essentially its too unreliable or too complicated. Picking a utility graph can be complex, but we’ll just use a simple one for now. See here for other considerations.

The utility graph can be different for each individual and based on many more factors then just how much of a good you already have. For example, the value of food may be proportional to hunger, or the value of a jacket based on how cold it is. But for now we will write the utility function for a good based only on how much of that good is already owned.

The general shape of the curve will be monotone decreasing since as we own more goods we value them less. But it can be interesting to try and imagine goods that have different properties. Consider if you had to buy pieces of a puzzle one at a time, then each piece you buy would not decrease in value, they might even increase a small amount as you get closer to finishing the full puzzle. But we’ll ignore these goods for now and just look at utilities that decrease in value as you have more of them.

Another property to consider is if the value of a good ever drops below zero. Can you have so much of a good that you would actually pay for someone to take it from you? These types of goods do exist, something like trash is something which the seller (buyer?) must give both the good and money to the other, while receiving nothing. This is not something we will consider right now, but is worth coming back to at some point.

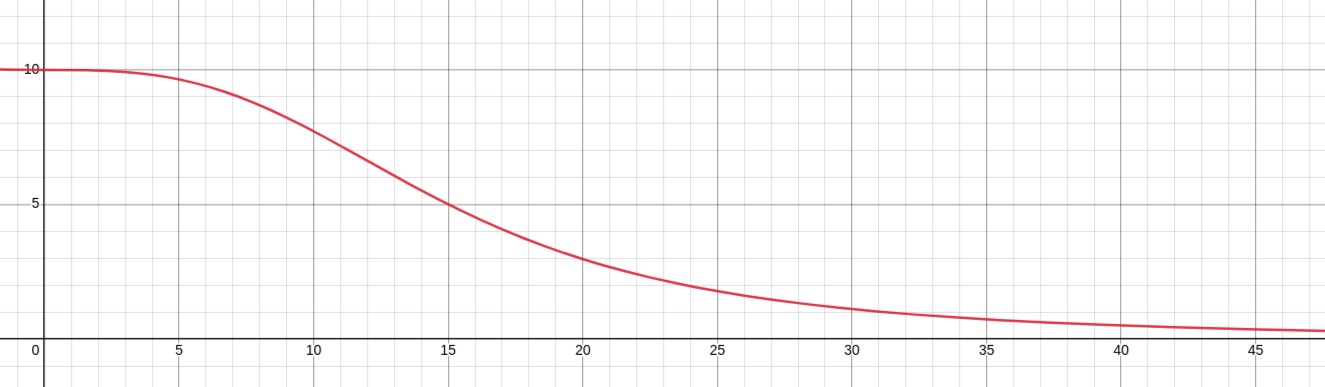

For now the utility graph will be defined by $\frac{S}{\left(\frac{x}{D}\right)^3+1}$ where $S$ is how much we value the first of that good, $D$ is how many of that good we want until it’s worth half its original value, and $x$ is the number of goods currently owned. Below is an example utility curve where $S=10$ and $D=15$.

But we face a new issue. Imagine an actor has an initial personal value of \$10 for a good, and when they buy one of that good, they now value it at \$8. This means they will initially buy the good for up to \$10, then be willing to sell it for as low as \$8, immediately losing money. This illuminates the fact that we don’t use a “current” value for a good, but instead use the change in value that an action will bring. So, we instead use two values: How much utility we currently get from a good (our sell price), and how much potential utility we could get from buying a good (our buy price). Since we have a decreasing utility function, the buy price will always be less then the sell price.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

// should not be called anywhere except from potentialValue and currentValue

func (actor Actor) personalValue(x int) float64 {

S := actor.basePersonalValue

D := actor.halfPersonalValueAt

// simulates diminishing returns

return S / (math.Pow(float64(x)/D, 3) + 1.0)

}

// returns how much utility you would get from buying another good

func (actor Actor) potentialValue() float64 {

return actor.personalValue(actor.ownedGoods + 1)

}

// how much utility you currently get from a good

func (actor Actor) currentValue() float64 {

return actor.personalValue(actor.ownedGoods)

}

This solves one problem, but uncovers another. The market still fails to converge to a price, but this time for a different reason. An actors expected market price changes until it falls into a range where the actor is neither a buyer nor seller. This is something we are familiar with. Consider the thought process “I would sell my current chair for \$40 since it’s useful, but I wouldn’t buy another chair for more then \$20. A second chair wouldn’t be as useful. The expected market price is \$30, so I am neither a seller nor buyer.” Once an actor enters this state, they no longer interact with the market and stop receiving market signals. In order to solve this problem we can simply send market signals to actors whether they’re in the market or not. This would be similar to you passing through a store and seeing the price of goods you may not care about. Although you aren’t participating in that market, you are still receiving market signals. We might also think of this as gossip, information naturally spreading between people. Once we add gossip, people can keep up to date on market values and interact with the market when it becomes advantageous. Another solution to this problem would be to have peoples personal values change over time until they decide they need to go to the market, which could be used in replacement of or in addition to the gossip.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// gossip

for otherActor := range actors {

gossipPrice := otherActor.expectedMarketValue

if gossipPrice > actor.expectedMarketValue {

actor.expectedMarketValue += actor.beliefVolatility

} else if gossipPrice < actor.expectedMarketValue {

actor.expectedMarketValue -= actor.beliefVolatility

}

break

}

Below is the graph of actors converging on a market price. Graphing the theoretical value from the supply-demand curve no longer makes sense since the supply-demand curve is incorrect. People now change their values (and willingness to buy or sell) dynamically with the number of goods they have. In order to correctly graph supply and demand curves we would need to extrapolate the number of people that would buy a good at price X, but that is difficult to say since some of those people may buy the good at less then X, and then would not buy at X due to diminishing returns.

We now have a roundless economy with limited supplies. This was done by replacing the rounds with a timer that tracks time spent failing to transact, then using diminishing utility and gossip in order to resolve the issues introduced by limited goods. The full repository can be found here.

Next

We only have a single good right now, what we want are a number of markets which can interact and influence each other. Goods also don’t get consumed or created right now, which is unrealistic. A simple economy of interacting markets we will create is a market for wood and a market for chairs. Wood is used to build chairs, so we would hope to see a coupling of the markets. Perhaps as the price of wood increases the price of chairs increase, or as the demand for chairs decreases the demand for wood decreases.