Water is wild, let’s see if we can recreate any of its properties from simulations at the “molecular” level. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves, this isn’t some complicated fluid simulation, nor are we developing anything as complex as molecular dynamics. Instead, let’s just take the most basic model we can think of and see how far that takes us (which is pretty far as it turns out).

Remove from your mind this idea of a complex molecule with atoms made of electrons, protons, and neutrons, with chemical bonds to other atoms, breaking and forming in chemical reactions, each molecule emerging with its own unique properties, laying the foundation of chemistry itself. No, our molecules will be dots on a screen.

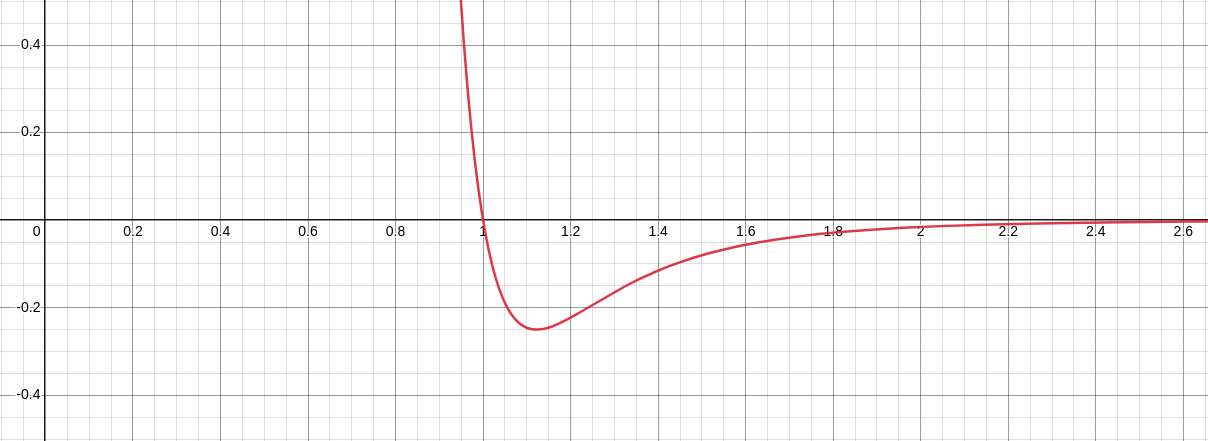

The equation for a molecule (a dot on the screen) interacting with another molecule will be $F=\frac{1}{x^{12}}-\frac{1}{x^{6}}$, where x is the distance from the other molecule, and F is the force. This means when the molecule is too close, it gets pushed away, and when it’s far, it gets attracted (but too far and it feels almost nothing, so we only have to think about molecules that are close). This is called the Lennard-Jones Potential.

Now, in every frame, each molecule will calculate its forces from every other molecule, then use $F=MA$ to update its acceleration, velocity, and position. If we take a look at a single stuck molecule acting on a single free-moving molecule, this is what we get.

Place a number of free-moving molecules together and you get a wonderful dance.

Phase transition

Place a large number of molecules together and you get chaos. But slow down the molecules over time, then they become more organized. In fact, at a slow enough speed, all the molecules come together and form a single blob.

If you squint your eyes, it almost looks like a gas turning into a liquid. This is exactly what we would expect from water as the temperature drops. When the temperature gets very low, you’ll notice the molecules start to form a crystalline shape, which is what we would expect from water if it got really cold. Unlike real water though, these molecules are still free to orbit around each other. They fail to “lock” into place, and so they maintain their liquid-like properties rather than turn to “ice”.

From the simple interaction of two individual molecules a hundred times over, we recreate something similar to the phase transition of water.

Cohesion

Run exactly the same simulation again, but with gravity.

If you kept your eyes squinted, you may see a water droplet now. This is acting like water cohesion, keeping the water together rather than having it spread out across the floor. It even has the same distinct bulging shape that water droplets have.

Surface tension

We now add rigid bodies made out of the same molecules. Every molecule is still exerting force on every other molecule, but the rigid body molecules are summing up their forces into translational forces and rotational forces, which act on the body as a whole.

Gravity will be turned on, and the temperature will slowly be turned up.

We see how temperature seems to affect surface tension, which makes sense since the water becomes less “solid” as the temperature increases. This is also seen with real water.

Buoyancy Force

By constructing hollow objects we can see a buoyancy-like force appear. We also vary the mass of the rigid body in order to probe how mass is related to the buoyancy force.

The rigid body molecules are heavier than the “water” molecules at all times, and yet the object still floats, why? Because the rigid body is hollow (more generally because it’s less dense), the overall weight of the rigid body is less than the weight of the water, so the water will push under and up, creating our upward force. If the rigid body becomes too heavy, the weight will be greater than the weight of water, so the rigid body will be the one pushing water out of the way.

There is an interesting behavior with the sunken box with its side flat against the floor. Even when the sunken box is made lighter, it stays sunken and refuses to float up. You can actually find this behavior in your bathtub. Take a very flat/smooth object, and push it against the bottom of the tub. The object sits there, failing to float up for longer than you might expect. Although, eventually it does float back up. This is because buoyancy comes from water pushing at the bottom edges of the object (think through why, find the weight up to the surface on the left and right side of the edge). Without the water underneath, the water molecules at the edge can’t translate their downward force into an upward force. The object in your tub isn’t perfectly flat, so eventually enough water gets underneath to start pushing it up.